9/11 Loved One’s Stories: ‘I Helped Save an Al-Qaida Terrorist from Death, Even Though His Plans Killed My Son’

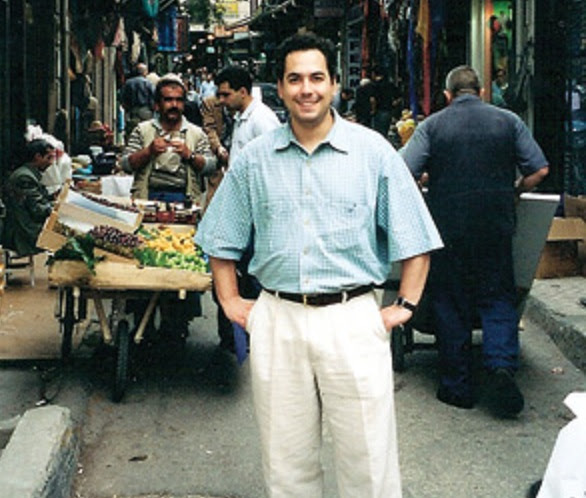

Greg Rodriguez, pictured in 2000Phyllis and Orlando Rodriguez

In the second of our interviews with 9/11 family members provided by Peaceful Tomorrows, we speak to Phyllis Rodriguez, who lost her son Greg on 9/11. Phyllis has since become a crusader for peace and tolerance, and played a lead role in helping convicted 9/11 plotter Zacarias Moussaoui from the death penalty.

Greg worked at brokerage firm Cantor Fitzgerald, on the 103rd floor of the North Tower. He had worked there for a few years, it was a good job, it was stimulating, albeit not something he wanted to do forever. He was recently married, to a wonderful woman.

On the morning of September 11 I had gone out early; I’d turned over a new leaf to take long walks in the morning. I’d left about seven thirty, and ended up going further than I planned. I’d planned to spend 45 minutes but I was out way over an hour. When I came home the porter in our building told me the World Trade Center was on fire. So I turned on TV and my answering machine. There was a message from Greg telling me there’d been a terrible accident but he was ok, and told me to call our daugfhter-in-law.

I called his office and cell phone. Nothing. Then I saw the second plane hit the south tower. I got in touch with all our family members and we were all worried. I guess my unconscious was avoiding the truth and protecting me, but I believed that since he left a message he must have been ok. When my daughter asked where he called from, I told her he must have called from outside the building, because who would call from inside a burning building?

The World Trade Center on fire on the morning of 11 SeptemberReuters

Evening came and we still had no idea whether he had survived or not. Like thousands of families next day, we visited hospitals, visited information centres downtown, we hoped he was being treated somewhere, but by the following evening we realised he hadn’t survived. The CEO of Cantor Fitzgerald got a large area at the Hotel Pierre in mid-town for families, employees and their friends to come for support. It was full of therapists, clergy, volunteers, and there were summaries of what they were finding. A computer bank was set up to track every single known person who worked at the company to see where they were.

That evening, September 12, the CEO announced that they had made a thorough search and concluded anyone who was not already located had perished.

We had to accept and deal with that. It wasn’t easy; I had never been in such a state of shock, physically as well as mentally. But we had responsibilities and I think they helped us in a way – we had three elderly parents living at that point, and we had to be conscious of them and how it would affect them. Our daughter, Julia and I supported each other, we became very close. The circle widened with my daughter-in-law Elizabeth’s family, and close friends.

We did a lot of interviews, my husband and I – the Daily News, TV stations, a lot of foreign journalists, alternative radio, talk radio. For me it made things better up to a certain point, I could do it, I was glad to get the message out. It was a way to follow our convictions. But after a few months the reality set in and we withdrew.

I would say it took a couple of years to get the shock and pain out of our system – it was a magnified version of what murder victims go through. We didn’t go to the scene, I wouldn’t say we had any rituals like that, although we did have a memorial three weeks after the event. What we had was each other, talking, we also had professional help, we realised we needed to speak to someone, and another thing was that we realised after the second plane hit, we’re not the only ones.

Turning off the TV

One thing we did do was get rid of our television, we didn’t want to see the media coverage or references to it, over and over again. I couldn’t laugh at humour that had nothing to do with the attacks, I was more sensitive to violence and cruelty, even something innocuous. Eventually we unplugged the TV and got rid of it, within four or five months.

We were also able to channel our feelings through campaigning and opinion-forming. As soon as the planes struck I knew it was going to be something that the government was going to politicise and I hope it was not Muslims. There had been another bombing in 1993 which was blamed on Muslims, and even the Oklahoma bombings in 1995 were blamed on Islamic extremists. We devoted a huge amount of time and effort to pushing our anti-war message.

My husband was a teacher at a Jesuit college in the Bronx, a sociologist and a criminologist. He and a colleague, a lawyer, created a course called terrorism in society to teach young people how to perceive what terrorism is and what it does, to get some understanding. Meanwhile we helped create Peaceful Tomorrows, in the hope of spreading a message against war. It stemmed from a letter my husband and I wrote in the few days after the attack, entitled ‘not in our son’s name’, which called for a non-vengeful response. After the letter was published we were put in touch with other families and through that we formed Peaceful Tomorrows, which is still going today.

Partnership with Aicha El Wafi

Separately I have worked with Aicha El Wafi, whose son Zacarias Moussaoui was charged with planning the 9/11 attacks. When we saw this man indicted and threatened with the death penalty, we spoke out through a murder victims’ families group. Its director had met a woman who was active in a French human rights group, and she often travelled with Aicha and was her interpreter.

![Phyllis Rodriguez [l] and Aicha el Wafi Phyllis Aicha](https://ci4.googleusercontent.com/proxy/vOFIOHjYdsKUbTqkee1wD0D2OGNXQx8EyklpnzhnTDi6zbIWnLhb1iqikzXiPlNtsB6skFvf2dSl_o5_E7gYFXzxFV7SuEPUnoNcAsfV=s0-d-e1-ft#http://d.ibtimes.co.uk/en/full/1398635/phyllis-aicha.jpg)

The director found out Aicha was coming to Alexandria, Virginia, to meet with her son and his lawyers, and he asked if anyone would be interested in meeting her. Six of us were interested. That was November 2002, and that time there was super-patriotism everywhere; we were scared that our meeting with the mother of the only suspect in custody would go public. So we met in a very private place, and from that we began to do media work together. We went public in 2005 when Aicha’s son was still in detention. That year he pled guilty but this left the second part, the sentencing hearing, which is like another trial – this took place in 2006.

The capital defender was looking for people to speak to the defence, to give ‘impact statements’, so my husband wanted to speak out in favour of him not getting the death penalty. He was one of 13 people who gave impact statements for the defence team. Three dozen did it for the prosecution. Their statements were all highly emotional and draining, because the prosecution wanted to get the sympathy of the jury. When the 13 defence witnesses testified, they said they could see the jury tense up. The result was that one juror voted against the death penalty, so the defendant got life imprisonment without parole. He’s still alive, and where there’s life there’s hope.

But look at what has happened in the last 13 years: warrantless arrests. Drone strikes. The stain on our reputation that is Guantanamo, a place I’ve visited and written about. There’s a terrible problem with Islamaphobia; we don’t have profiling of white, blue-eyed men in this country, and yet we have extremists in every community. It’s in the names of the victims of 9/11 that this bias is maintained. And then there was the campaign by Bush and Blair, which made the grieving process worse – the feeling of our son’s life being exploited for prejudice.

I’d say right now we live with the loss, it’s always there, but we can carry on normal positive lives. Sometimes the pain surfaces, it’s like a scab that never heals completely, and it’s an acceptance and we deal with it. We feel very fortunate we have so much support for family, friends, community, and people to share the grief.

For more information about the aims, objectives and campaigns of the Peaceful Tomorrows organisation, visit their website by clicking here.